This idea has persisted among the villages near the tomb, where they say that no one should enter the tomb; but in spite of ‘Ibn Al-Balkhi’ and the ignorant ideas of the peasants so far everyone who has entered the tomb to view it has returned safe and sound.

Scholars are of the opinion that civilizations began in valleys and beside rivers, and afterwards spread to hill centers, for the preparation of cereals and other foods, and the care of flocks and cattle require of abundance of water, land and grazing grounds. Therefore the banks of rivers afforded the most suitable place for the building of houses, the setting up of communities, and the assuring of the simple requirements of life of the people of those days.

Moreover they were not threatened by the recurrent danger of famine as the dwellers in the hills and plains were. And when it happened that the banks of rivers were near the hill districts, the inhabitants were in a very good case, for they were not only at ease as far as the securing of the means of their own livelihood was concerned, but were well situated in regard to grazing areas on the mountain slopes for their animals.

The plain of Pasargadae possesses just these advantages, for low hills surround it, and two sufficient supplies of water, the Pulvar and the Morghab irrigate it.

Facing the tomb of Cyrus the Great at a distance of three kilometers to the south-west there is a long and deep gorge called the ‘Bulaghi’ pass, through which the Baseri, Kurdshuli, Farsi, and Arab tribes migrate. As this pass is the nearest way between Qaderabad and Sivand the tribes refered to at the time of migration to the cooler regions, and when returning, use this route. The length of the pass is about 12 kilometers and the width 200 to 500 meters, but this space is not fit for passage, as the River Pulvar, and a quantity of trees on both sides of the river impede progress, and it is necessary to pass by way of a narrow track on the side of the mountain. This narrow pathway alter passing four bluffs known as Sangbar, ‘Na’lshekan’, ‘Tirandaz’ and ‘Puzehye Surkh’ debouches into the wide plain also bearing the name of ‘Bulaghi’.

At the beginning of the pass (starting from the Pasargadae plain) a narrow pathway has been cut out of the mountain side a meter and a half or two meters wide, and almost 200 meters long, and this is worthy of notice, what remains of it indicates that it belongs to a very remote age, and afterwards as became necessary through much coming and going, they deepened and widened it in places as much as ten meters leaving a stone wall on the outer side. The ‘Bulaghi’ pass is parallel to the ‘Sa’adat-Shahr’ one, but whereas the ‘Sa’adat-Shar’ Pass is dry and lacks water and vegetation, the other one, like the ‘Firouz-Abad’ Pass is full of trees and is green and pleasant. Undoubtedly the road connecting Persepolis and Pasargadae with Ecbatana (Hamedan) lay through this pass.

Prehistoric Remains in the Plain of Pasargadae

The wide, well-watered and fertile plain of Pasargadae bears evidence of the continuous existence of an old ancient civilization in this area, which persisted until the early days of the rise of the Achaemenids. This view is generally confirmed by the fact that many of the great places and buildings of the olden times were set up in places which were formerly inhabited by, who have themselves in their turn left traces of their own skilled industries. In many corners of the Iranian plateau pre-historic mounds abound, the most ancient of which are the Siyalk mound of Kashan, the JafarAbad one at Susa, and the mounds at Marvdasht, where in the course of excavations remains dating from the fifth millennium before Christ were found, so far preceding other remains.

Of course there are other mounds also in the neighborhood of the mounds referred to and in other districts, where excavations have taken place, and remains belonging to the fourth third and second millenniums BC have been found. Bearing in mind that all inhabited places, where ancient peoples dwelt were situated beside streams and rivers, the existence of the river Pulvar to the east of the buildings of Cyrus, and in the center of the Pasargadae plain confirms this view and assumption, and in addition to the excavations carried out in the summer of 1951 removed all uncertainty on this point. The existence of a settled population and the agricultural and strategic situation caused Pasargadae to become the center and eventually the capital of a number of tribes and peoples. In the same way Persepolis also took its rise in the midst of numerous pre-historic mounds, and acquired the position of the Persian capital.

The discovery of these pieces of pottery proved that more than four thousand years before Christ tribes and peoples lived in the plain of Pasargadae, and their arts and crafts resembled and developed alongside those of contemporary peoples. The colors of the designs on the pottery are light and dark brown, dull red, olive green and black.

Pre Achaemenid remains at Pasargadae

In the course of removing soil from the stone platform, known as ‘Takht-e Soleyman’ (The Throne of Solomon) pieces of black pottery resembling the pottery of Elamite period, and a piece od stone bearing the carving of the back hair of the head of a statue were found, which most probably display Elamite art. But unfortunately during the changes and upheavals of the past centuries the remains at Pasargadae have suffered much injury, and all the carvings have been broken or carried away to other places when buildings for peasants were erected. For this reason throughout years of excavation, no pieces of stone carving have been discovered in sound condition. Occasionally we have found pieces of stone carving in the ploughed areas some distance from where they belonged.

The influence of the Elamite civilization and arts belonging to the second millennium before Christ can be seen in the carvings at Kurangan in the Mamassani county, and at the Hajiabad mound (Naqsh-e Rostam), where there are the most ancient carvings discovered in Fars province. The late professor Hertzfeld, who found them, was of the opinion that the carvings referred to belong to the millennium before Christ, and testify to the artistic independence and development of Iran in the very ancient past.

The remains at Kurangun and Naqsh-e Rostam are recognized as subject to the influence of Elamite art in that the king is depicted seated on a snake throne with a crown and two horns, and this kind of carving is traceable to pre-Akadian and in fact Sumerian art which left its impression on Elamite art. A somewhat similar design on a cylinder seal was found during the excavations of the Siyalk Mound (Sialk Tapeh) at Kashan which shows the God bearing a cup in his hand from which water is flowing towards his servants. The discoverers date this 2400 BC.

The last resting place of Cyrus the Great

‘O man, I am Cyrus Son of Cambyses, founder of the Persian Empire, and king of all the east, grudge me not this tomb’

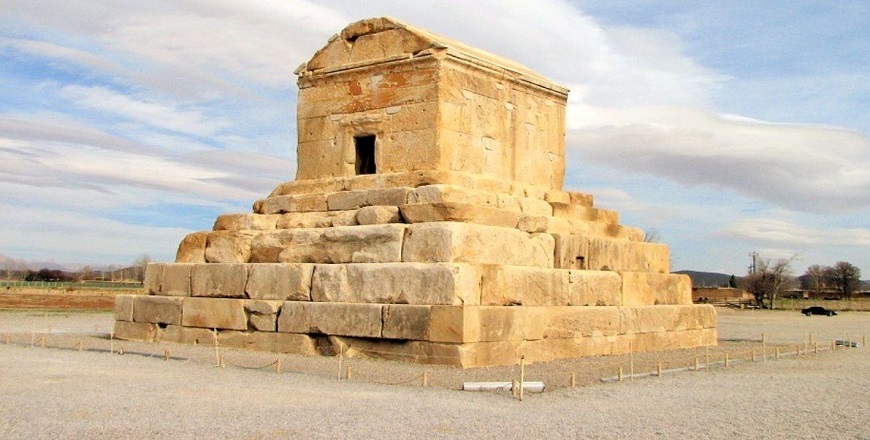

When approaching Pasargadae the first monument which attracts the attention of the traveler, and which can be seen from several kilometers distant is a fine stone building, which almost 2500 years ago was the tomb of Cyrus. The tomb contains a room 3.5 meters long and 2.1 meters wide. The walls, floor and roof are of huge blocks of cut-stone. The entrance, which has a narrow dark passage way, opens towards the west. This room stands on six tiers of massive white stones resembling marble, and the whole rises to a height of 11 meters from the ground. The interior of the tomb bears traces of a prayer-niche ‘mehrab’ and an obliterated Arabic inscription belonging to the Islamic period.

The exterior is extremely simple in design, and yet stately and impressive. The stones of immense size attest the capacity and intelligence of the builder. The white stones were shaped and fitted together with the utmost care, and were attached to one another by iron clamps in such a way that after being forgotten for 25 centuries they still stand in mountainous fashion, and will stand firm for centuries to come when we are dust, and will survive the onslaughts of wind and rain. The interior of the tomb has now no ancient inscription, but according to the statements of most of the Greek historians such as Strabo, Arian and Plutarch there were inside the tomb two tables bearing inscriptions in cuneiform as follows:

O man, whoever thou art, and whenever thou comes, for I know that thou wilt come, I am Cyrus, who made this wide empire for the Persians.

Grudge me not therefore this handful of earth which covers my body.”

“O man, I am Cyrus son of Cambyses, Founder of the Persian Empire and king of the east. Grudge me not this tomb.”

In the Islamic period when the tomb was turned into a mosque, a prayer niche was carved in the southern interior wall, and some words also were inscribed there. In regard to this inscription one of the former historians has written that he had seen among the Arabic words the term “Martyrium” of the mother of the prophet, but today nothing can be read of it.