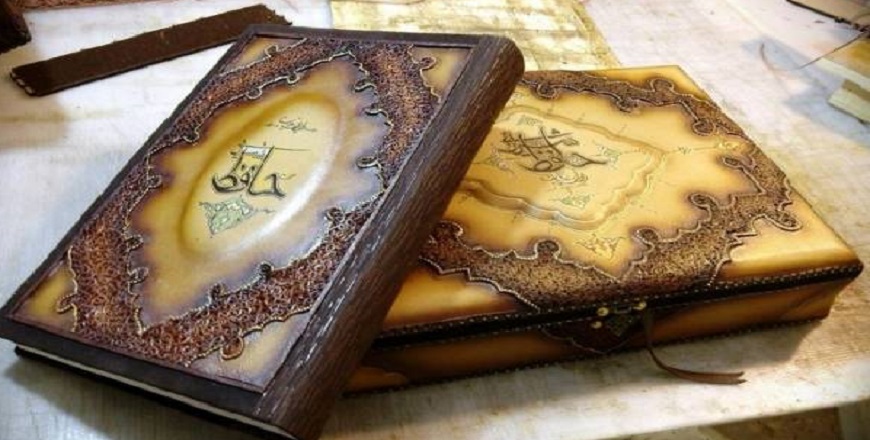

In this journey we are going to see English translation of some thirty Persian poems plus brief notes about the poets. The earliest of the poems dates from the first half of the tenth century AD, the most recent from the twentieth: thus a span of a thousand years. They are written in the classical Persian tradition, strongly influenced by Sufi thinking about life, although not all poets were Sufis. Some of these poets are among the greatest and best loved, still cherished and quoted today in the homes, streets and squares of Iran. Persian has changed less than English over this period, so that the poems are much more accessible to the public at large than Chaucer to English speaking people, let alone Beowulf, an still part of a live, oral tradition.

It is important to recognize one general, though not complete, difference between Persian and English poetic conversations. Usually, an English poem develops a story, a line of thinking, or an argument. Think of Shakespeare sonnet as an example. In Persian, by contrast, each stanza is an independent thought or image on the poem’s theme. Consequently, there may not be narrative progression from verse to verse. Rather, the relationship among stanzas is more like of facets of a cut stone, together making a jewel.

One of the joys of studying these Persian poems is that the imagery is unfamiliar to us, and can strike us with freshness and surprise. Take for example, the verse in one of Hafez’ poems:

“When spring brings life to the meadow’s edge, you sweet bird

Will draw the rose’s parasol to shield your head. So do not grieve.”

Or in another poem speaking of his body as a cage:

“Such a cage is not worthy a bird who sings so sweet:

To paradise I’ll fly, for that meadow’s my true space.”

Or take Rumi, in the opening lines of his passionate poem to Salh-Alddin:

“ Veiled like the soul, making me whole

You enter my heart

Elegant as a tree, delighting me,

You stand apart.

Slender and tall

With a garden’s art”

It is worth nothing that, as in the Persian visual arts, such as painting and ceramics, many of these images are drawn from gardens, which were loved both for themselves and precursors of Paradise.

The poems we are going to read are often very direct and to the point. One can think of Rabia’s vitriolic attack on a faithless boyfriend, or Ansari’s dialogue with God, remonstrating that mere justice is not good enough from God to man. For some other poems a broad understanding of the Sufi tradition in Islam is helpful. It originated soon after the Prophet Mohammad’s death, with ascetic followers of the prophet, seeking lives of poverty and abstinence. This was a time when, in the turbulent world of Arabia and the Middle East, Islam was expanding rapidly and was drawing in converts from other religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Zoroastrianism. These sometimes brought their earlier associations with them.

Sufism tended to set its face against a rule-bounded, hierarchical interpretation of Islam, and instead emphasized the pursuit of mystical union with God, channeled through a spiritual guide and Mohammad, the prophet. The relation between pupil and teacher was crucially important and leaving-centeredness behind in the pursuit of a fuller and more profound version. Sufism is marked more by diversity and ambiguity than by homogeneity, and was often at odds with clerical authority. What these poets believed is to be found, or puzzled over, within their poems. A common theme is the need to transcend oneself and worldly pursuits in order to seek God through love.

Thus Sa’di:

“If you are man of love, think less of yourself,

Otherwise take the easy way, absorbed by self

Don’t fear love, though it consumes you utterly:

Even though it destroys you, it gives life beyond death.

The plant does not grow at once from the seed:

First its sense of the world must be transformed.

What allows you to perceive divine truth

Is precisely what frees you from yourself.”

Alongside this emphasis, there is contempt for those who mistake their path. Thus Bidel:

“Don’t delude yourselves that you

Are arriving close to God.

As you’ve never escaped yourself,

Where could you have gone?”

The aim is to reach out towards God. As Hafez says, at the end of one poem:

“My heart bleeds, scented with Divine desire.

My agony is like the musk deer, whose perfume costs its life.

Though clothed in spun-gold, I am not soft candlelight,

Beneath my robe of honor, burn flames you cannot trace.

Come, lift Hafez up from his being and himself,

Once I have found You, no one will hear me say “I am”

Finding God may not be easy, however. The Old Testament prophets can help, as can Jesus and Mary, and most of all, for Muslims, The prophet Mohammad

God also sought and found through the world that he created; hence, Sa’di:

“I rejoice in the world because of this:

Because the world comes rejoicing from God.

I am in love with every star in the galaxies

Because the whole wide world is His.”

And through human beauty; Iraqi:

“In the beauty of lovely faces, I saw Him made plain

In the flash of exquisite eyes, the beauty I saw was Him.

Love is very common theme for them. Sometimes is the love of God, sometimes human love, which maybe physical or spiritual, or a mixture of all of these. Ecstacy is another common theme, often associated with imagery of wine-drinking, dancing and wild behavior. Clearly this could not be countenanced within orthodox Islamic rules, unless the wine and the behavior are to be interpreted figuratively, not literally. Even today, when these poems are still immensely well-known and popular in Iran, the argument as to whether they are about divine or human love, and about transcendence, not indulgenece, is alive and well.

At one extreme, some of the poems can be taken as metaphysical, in a similar sense to, say, John Donne and Henry Vaughan. At others (like Donne indeed) they are less exalted, saying simply that all we can be certain about is our life and love in this world. What follows afterwards, if anything, no man can know until the moment of his death, and then there is no coming back. Take Naser Khosrow’s poem as an example:

“Discomforts and trials in this world are long drawn out

Yet agony and joy will certainly one day cease.

Haven’t wheel travels on for us day and night

Behind each comes the next, following in its trace.

Here we travel and complete our voayagings

Until our journey after death begins.”

Or Khayyam:

“The mysteries of eternity, neither you can know, nor I.

The cryptic letters, neither you can decode, nor I.

It comes from behind screen, our converse, yours and mine,

And when the curtain falls, neither you remain, nor I”

The translated poems we’re going to read here are examples and part of a rich Persian culture, as much valued in Iran today as at any time in the past, and because they show a side of Islam that is about love, not hate, searching, not certainty. Inevitably, the English versions fall short of the original, for Persian has a beauty of the sound that cannot be matched in English. Nevertheless, they are better known in translation than not at all.